Episode 5 | Was The Colosseum Anything Like It Is Portrayed In Gladiator?

Blood and sand, the clash of steel, the roar of the crowd. But what was the Colosseum really like? Let’s find out in this week’s instalment of History vs Hollywood!

The Film Narrative

Saved from death, our Knight of Rome, saved, but delivered into bondage. In and out of consciousness he fades as he is transported to a faraway land. A land, sun baked and blood red. Here he will find his destiny.

Awoken and forced to fight, a Gladiator he becomes. Guided by those who have gone before and supported by his new brothers, he cuts his way through his opponents, bellowing to the banal onlookers, “Are you not entertained?”

But entertained they are, The Spaniard they hail our Knight, hail him and carry him to the great white city on its seven hills. Our Knight, comes to the centre of the world, to fight and die in Rome.

Every enemy he faces falls beneath his blade, every foe conquered by the Knight and his Brothers, the Spaniard is the toast of the city. Empereros, senators and children all know his name.

The emperor Commodus, murderer of his noble father and sponsor of the games that have built our Knight’s fame, steps onto the sand. “Remove your helm,” he calls.

The helm removed, reveals Commodus’ treachery, as our Knight swears an oath of vengeance, for Rome, for his wife and Son, that in this life or the next.

The match is set. The die is cast. Who will the Gods favour?

A bit about the newsletter…

Welcome to History vs. Hollywood, the newsletter for film and history enthusiasts alike. Each week, we take a deep dive into the real events behind some of the most beloved historical films. We’ll go through the story, scene by scene, and reveal the truth—separating fact from fiction with the help of leading historians.

Whether you're a keen history buff or simply enjoy a good period drama, this is your chance to explore the fascinating realities behind the films you love. It’s not about dry lectures, but rather an engaging journey through history, with a fresh, cinematic lens. Not to mention our entertaining original artwork.

Best of all, it’s completely free. If you enjoy what you read, I’d be ever so grateful for your support—whether it’s subscribing, liking, recommending me to your own readers or sharing with others who might appreciate it. So, join us as we uncover the real stories behind the silver screen.

The Real Historical Narrative

Hello and welcome back! This is part two of a three-part series on Ridley Scott’s absolutely fantastic Gladiator. If you’d like to catch up on the previous episode, you can find it here. I’m incredibly excited to delve into the real history behind the film, as it has been a favourite of mine for years.

In this second part, we’ll step away from the film's narrative and focus on the Colosseum! We’ll explore what it was really like, who fought there, what it would have been like to watch the games, why they were held, and, of course, whether the Colosseum is anything like how it’s so brilliantly portrayed in Gladiator. So, let’s dive in!

Before we begin, I’d like to give a big shout-out to my source for this episode: The Colosseum by Keith Hopkins and Mary Beard. It’s a fantastic book, full of colour, and as brilliant as anything Mary Beard puts her pen to. I’m in no way affiliated with either author, but if you’re interested, you can get hold of a copy here.

Gladiator, as the name suggests, involves a great deal of gladiatorial combat—staged deadly battles between slaves in an arena, most spectacularly in the Colosseum in Rome, or the Amphitheatre as it was known to the Romans. Inaugurated by Emperor Titus in 80 CE, the Colosseum remains today one of the most potent symbols of Ancient Roman culture. Thousands of people travel from all over the world to walk its halls and archways, imagining what it would have been like to witness its events at the height of its glory. The grunts and cries of dying warriors, the roar of exotic beasts, and the deafening cheers of the crowd, all amplified by bloodlust, are difficult for us to fully picture.

Perhaps this is why films like Gladiator resonate so deeply with us—they transport us back in time and confront us with uncomfortable questions. Would we have gone? Worse still, would we have enjoyed it? I think that’s what makes the topic so compelling, and why people from all over the world are drawn to the Colosseum—the unsettling suspicion that most of us probably would have gone, and called for death, and howled in anguish when a favourite fell, or a jumped out of our seats in celebration when we had picked a winner. Who knows? Hopefully, our own civilisation will not devolve to such a point where we are confronted with the opportunity to witness similar events. Anyway, on with the story.

Some have argued that the significance of the Colosseum in Roman times is a modern projection, suggesting that we’re simply trying to make the Romans seem more thrilling than they actually were. But, to be honest, that’s complete nonsense. You only have to look at the massive number—around 200—of similar structures found across the Roman Empire to see that it was a huge deal. But Romans had been getting their kicks watching people fight to the death long before the Colosseum opened.

As mentioned earlier, the Colosseum was opened in 80 CE, so where were the Romans were getting their fill of gory entertainment before that? Gladiatorial combat had been happening for some time by 80 CE, and interestingly, Rome was one of the few major settlements in the empire without a dedicated venue for the fights. They often took place in the Circus Maximus, or occasionally, a wealthy Roman would construct a temporary arena in a location like the Forum for a special event. It wasn’t until the reign of Vespasian, the victor of the 'Year of the Four Emperors,' that anyone considered building a permanent structure.

Vespasian demolished one of Nero’s ridiculous building projects—a massive lake in the middle of Rome—and in its place began the construction of the Amphitheatre. Fortunately for him, he had just returned from successfully crushing a rebellion in Judea, providing him with plenty of slaves to throw at the job. However, Vespasian would be long dead before seeing his work completed.

In the meantime, across the empire, men (mostly men—more on that later) continued to die in gladiatorial combat. The original idea for gladiatorial combat appears to have been a quasi-religious ceremony, meant to appease the spirits of the dead, with the earliest records of such events found at funerary rites in the Bay of Naples region. It was more than just entertainment. There were punishment executions, likely intended to reinforce the power of Rome in the eyes of the spectators; wild beast hunts, not only to entertain but to showcase the vast territories over which Rome held dominion—elephants from Africa, bears from Scotland, and so on; and, finally, there were the gladiator fights themselves, spectacles and rituals to honour the dead.

Far more than just a sports stadium, the Colosseum was also a political theatre, where the ruling emperor could stage shows that could make or break his reputation with the public. It represented Rome’s highly stratified society in microcosm, with the Senate seated at the front, followed by the Equites, and so on, until the worst seats at the top were filled by women and slaves. The one thing that connected all levels of society was their right to attend—a detail that was very much by design. They were all Roman Citizens, and had equal rights of attendance, some were just more equal than others.

The inauguration of the Colosseum itself had special significance. Titus opened the Colosseum in the aftermath of the eruption of Vesuvius and the destruction of Herculaneum and Pompeii. This cataclysmic event had horrified Roman society, which, convinced they had offended the gods, was stricken with doubt and anxiety. Titus was well aware of this and knew he had to make a statement. He understood that a city in order was a happy city, where everyone had their place and remained there. This is why the Colosseum’s seating arrangements were so important. The order, and the bloodshed offered to the gods within the Colosseum, would reassure all of Rome that they were safe and that the destruction of Pompeii was a thing of the past. Rome had survived and could look forward to a brighter future.

Over the centuries, we hear of prolonged orgies of bloodshed held by various emperors. Titus inaugurated the amphitheatre with games that supposedly lasted 100 days. Thousands of beasts, gladiators, and prisoners would have died, but unfortunately for us, no exact records remain. Moreover, numbers from ancient times should always be taken with a pinch of salt, as the Romans were famous exaggerators. It’s unlikely that 100 consecutive days of watching people being killed would have been bearable for anyone, so it is now commonly assumed that the games were not continuous, but rather held sporadically. Perhaps on the weekends, not that the Romans really had those, but you get the idea.

The games likely followed a common schedule, with beast hunts in the morning, executions over lunch, and the climax of gladiatorial combat in the afternoon. Occasionally, they would vary the programme with special events, such as mock naval battles. However, the idea that these took place inside the amphitheatre seems far-fetched; it’s more likely they were held on a suitable, nearby body of water.

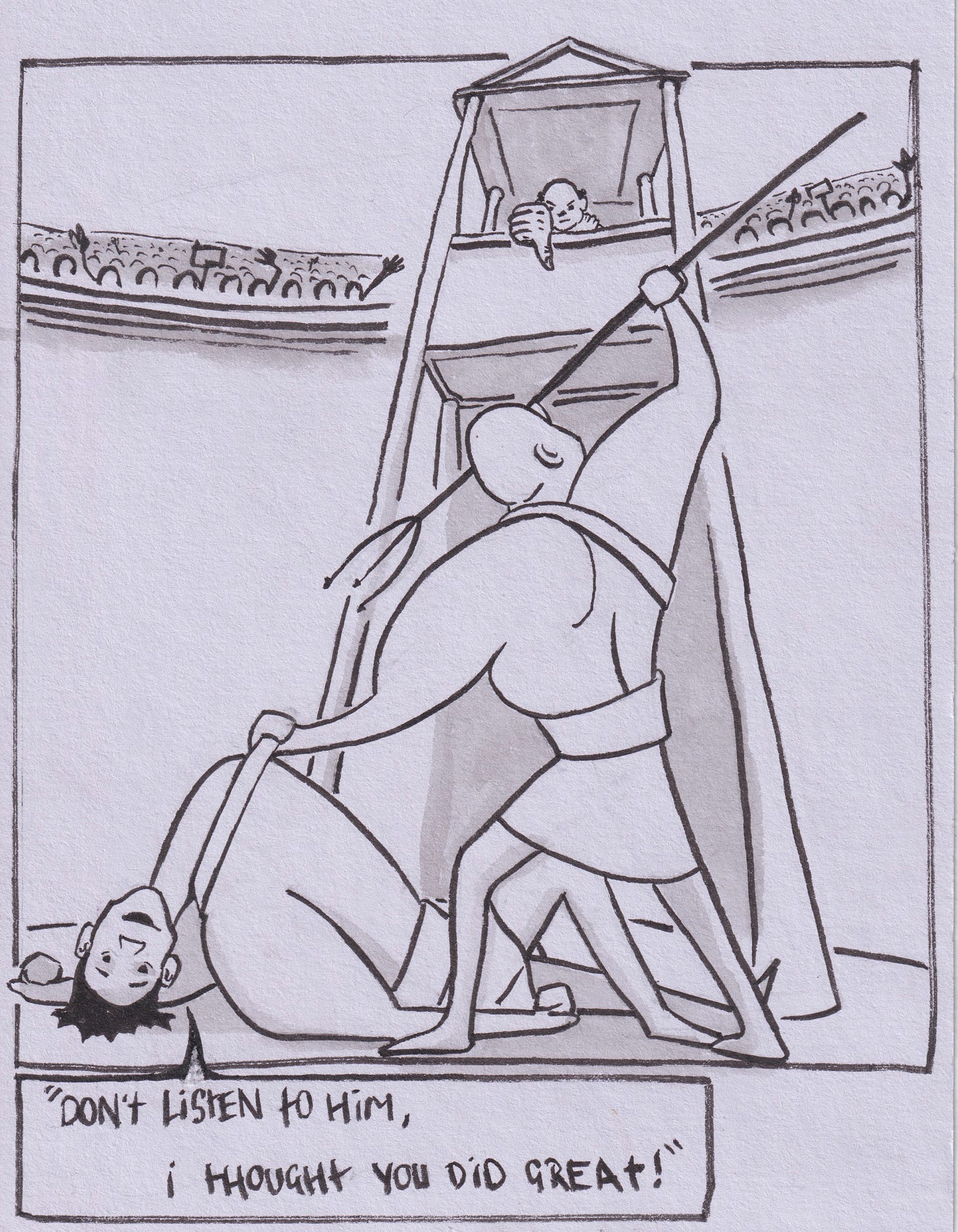

It is hard to grasp exactly how a gladiator fight went as we have no surviving accounts from anyone who fought in one, but it may have gone something like this. Lunch ends, and to the blast of trumpets, the gladiators are led out into the arena (the word "arena" coming from the Latin word for sand, harena). They parade around in ceremonial garb, are presented to the emperor, and then head back inside. The first bout begins: a net-man, a retiarius, and a fish-fighter, a murmillo. They touch gloves, so to speak, and then it is on. The heavily armed and armoured murmillo dashes into the attack, hacking with his gladius, while the lightly armed retiarius dances away, out of reach. Cut and dodge, cut and dodge, this goes on, back and forth, with the murmillo trying to close in on his nimbler opponent, and the retiarius staying out of reach, waiting for an opportunity. The crowd’s excitement builds, and their coaching staff shout encouragement from the sidelines. The fight continues, but starts to drag on a bit, both fighters know they are there to put on a show. Whilst the retiarius is distracted by that thought, the murmillo feints one way and then slashes another, catching the retiarius with a glancing blow on the upper arm. Luckily, it is only superficial, the crowd lets out a collective exhale. In his head, the retiarius berates himself for being complacent and uses the sting of pain to regain focus. The quick strike by the murmillo has cost him however, heavily armoured, he tires quickly as the bout continues. He makes a mistake, slow to regain his guard after a reckless thrust. The retiarius steps aside and thrusts his trident into the murmillo's exposed flank. The crowd gasps. Quickly, the retiarius seizes his advantage, covering the murmillo with his weighted net. He yanks his trident free and stabs again, this time through his opponent’s thigh. Down crashes the murmillo, his blood beginning to seep into the sand. Victorious, the retiarius turns to face the crowd, raising his arms to bring the roar of the crowd to a crescendo. For a moment, he bathes in the adulation before turning to the emperor’s box, silently asking the question that will decide the murmillo's fate. At his feet, the murmillo, accepting that death is inevitable, exposes his neck. The emperor gives his consent, and the retiarius’ blade flashes, the murmillo’s life blood flows, a sanguine herald to the end of his career. The crowd roars.

Perhaps that was what it was like, perhaps not, as I just made that up. Whatever did happen in the Colosseum would probably be hard for modern viewers to stomach. One of the first 'acts,' described in a poem by Martial, who was supposedly an eyewitness to the opening of the Colosseum, involved the recreation of a story from mythology. This was the tale of King Minos of Crete, whose wife, under Poseidon's influence, fell in love with a bull, eventually giving birth to the fabled Minotaur. The Romans decided to re-enact this by having a woman (see, I told you it was only mainly men) dragged into the arena, bound in some way, and then mounted by a bull—to death. The logistics of this are beyond my expertise, but it was presumably part of the executions segment, meaning it was during lunchtime. Martial gives the whole event a glowing review in his poem, but I imagine most of us would lose our appetite if that were a lunchtime intermission today.

Executions, like the one described above, were often staged to be a sort of snuff film retelling of a beloved myth. We hear of other gruesome demonstrations, such as a condemned man having his arm roasted over a fire to represent a legendary figure of the early days of Rome, who had supposedly done this to show how tough he was. There was the mythical castration of Atys, which means I assume some poor bloke was gelded in front of the crowd. Also the mythical tale of Hercules self immolating to go up to heaven, and I am sure you can all guess what happened there. All this brutal pageantry was a way of confirming the Romans as one people in their shared culture, as well as acknowledging the justice of their laws.

So, what must it have been like to step out onto the sand of the Colosseum? Thanks to the magic of CGI, those who have seen Gladiator likely have a fairly consistent idea: 50,000 spectators calling for blood, hundreds of gladiators clashing, sweat and blood spilling. To the Romans, it must have truly been a spectacle on an epic scale. For modern viewers, however, it might have seemed a bit underwhelming. The Colosseum is actually significantly smaller than it appears in Gladiator and certainly much smaller than most modern stadiums.

Ridley Scott is said to have been inspired by the painting Pollice Verso by Jean-Léon Gérôme. The painting depicts a victorious combatant standing over his vanquished opponent, in what seems to be an enormous stadium, and includes many elements we associate today with the Colosseum. In fact, the painting has been far more influential than we might initially realise.

For example, we have the image of the bare-breasted, helmeted victorious gladiator. From this, we derive the typical portrayal of a gladiator—helmet, pecs, and all. The problem is, we actually have no hard evidence that gladiators ever wore helmets like this while fighting. In the ruins of Pompeii, an almost perfectly preserved murmillo helmet, similar to the one depicted in the painting, was found in the gladiators' accommodation. Because of this, over the centuries, we’ve assumed that this was the type of helmet these gladiators fought in. But that’s all it is—an assumption. Perhaps these helmets were ceremonial or some sort of trophy.

Not only was the one found highly elaborate, showing no signs of battle damage, but it was also monstrously heavy—about twice the weight of a Roman legionary’s helmet. This doesn’t necessarily mean they didn’t wear them, but we simply can’t be sure.

The same uncertainty applies to other aspects of the painting. The famous "thumbs up or thumbs down" gesture, believed to signify life or death for the vanquished, is another example. Despite how much we might like to believe we know which gesture meant life and which meant death, there is no definitive evidence confirming either interpretation.

I’ll give you a few more examples. The idea that the Colosseum was strictly segregated by class and gender is widely accepted—until you hear stories like that of Emperor Domitian, who supposedly had a sort of gory meet-cute with his future wife at the games. Such an encounter would have been impossible if women were truly segregated from men into their own area.

A note on Domitian—although he was a fairly unpleasant figure, he did have a certain dark sense of humour. He was supposedly a fan of the murmillones, similar to the gladiator in the painting, who were apparently a faction of sorts. On one occasion, while at the games, Domitian overheard someone in the crowd suggesting that it was impossible for their favourite faction, the Thracians, to win with Domitian supporting the murmillones. In typical Domitian fashion, he had the man dragged from the crowd and thrown to the dogs in the arena, with a sign around his neck that read something along the lines of, "It’s okay to be a Thracian fan, just don’t be a dick about it." That must have been quite a day for the crowd!

Supposedly, gladiators had a public meal the night before a fight so that prospective gamblers could come and inspect them before placing their bets. Again, there’s no concrete evidence that this was the case—perhaps they did eat publicly, but we have no proof that it was for the benefit of gamblers. This is simply an assumption made by modern historians, drawing parallels between the games and activities like horse racing.

The age-old trope of Christians being fed to the lions actually has no concrete evidence. Now, before I go any further, I’m not saying that it never happened—it very well could have—but we simply don’t have any evidence for it. Christians in the later centuries of the Roman Empire loved to tell stories of their predecessors being thrown to the lions. Each tale came with some sort of moral lesson about how the Christians refused to give up their faith and stood bravely in the face of gruesome death, or how a noble and chaste Christian woman made sure to readjust her clothing so as not expose herself after being mauled. But that’s all we have—stories shared centuries after the fact, with no evidence to support them.

You also have to consider who benefits most from the tales of Christians being fed to lions. In the early stages of Christianity (and some might argue, even today), it was important for the religion to be seen as persecuted. And what better example of persecution than being thrown to a lion? I mean, that’s pretty metal! Again, it could have happened, but the narrative certainly benefits Christians by reinforcing their image of martyrdom.

Finally—and I’m sorry to disappoint fans of Gladiator, because let’s face it, it’s a really cool part of the film—it’s extremely unlikely that anyone ever uttered the phrase “Those about to die salute you” in the Colosseum. The only record of this phrase being said was during a naval battle staged by Emperor Claudius. Supposedly, the unfortunate combatants came out and shouted it across the lake at Claudius, who is said to have mumbled a weak joke in response, something like, "Well, you're not all going to die." The gladiators, thinking they had been pardoned, dropped their weapons and refused to fight. Claudius, already a frail old man, then had to get up from his chair and harangue them into killing each other. Quite embarrassing for Claudius I imagine.

As entertaining as this story sounds, it’s also quite improbable. What are the chances that gladiators on a boat in the middle of a lake could hear the mumblings of an old man on the shore, presumably some distance away?

What we do almost certainly know to be true about gladiators, however, is that they absolutely oozed sex appeal. Not unlike Russell Crowe himself, people were attracted to gladiators. As the old saying goes, women wanted them, and men wanted to be them. In fact, men clearly wanted to emulate them so much that, at one point, the Senate passed a law prohibiting those of senatorial class from participating in the arena as gladiators. This didn’t stop a few emperors stepping out of their boxes and into the arena, but we’ll cover much more of that in next week's episode on Commodus.

There is plenty of evidence to suggest that gladiators were looked down upon in Roman society. Not only were they primarily slaves, but the word "gladiator" was also apparently used as an insult by upper-class Romans to belittle one another. On the other hand, there’s also plenty of evidence to suggest they were highly admired and often lusted after. From the mountains of artwork and artefacts portraying scantily clad gladiators fighting, to graffiti in Pompeii referring to gladiators as “the heartthrob of the girls” and “king of the dolls.”

We even have salacious rumours about Marcus Aurelius’ wife, Faustina, mother of Commodus, having had an affair with a gladiator, which supposedly led to Commodus’ birth. One account suggests that upon hearing this, Marcus consulted a soothsayer, who advised him to kill the gladiator, make his wife bathe in his blood, and then have sex with her. Supposedly, he followed this advice and raised Commodus as his own. As tantalising as this tale is, it seems unlikely and was probably an attempt to explain why Commodus was so obsessed with the Colosseum.

The Roman word for sword, gladius—part of the word "gladiator"—was supposedly Roman slang for "penis." Whichever way you look at the evidence, one thing seems clear: plenty of Romans likely spent the long hours of the night fantasising about bare-chested gladiators and their swords.

Outside the arena, gladiators may have been getting some action, but there was plenty of it inside the arena too. However, the attention outside doesn’t seem to have been enough to convince those inside that it was all worth it. We are almost completely missing evidence from the gladiators' point of view in the historical record, presumably because they died before they could put their story to paper or papyrus, or something like that, but also because no one seemed to care to ask what they thought. Perhaps it was easier for the Romans to view them as opinionless sex objects, than to consider them as real human beings. We can, however, infer a few things from stories passed down through the ages, and they paint a grim picture.

One story refers to 29 Saxons who, having been transported to Rome to fight, strangled each other the night before their show to avoid the horrors awaiting them—or perhaps to deny the Romans the satisfaction. Another tale tells of a German gladiator who, before the show started, went to the toilet, understandably nervous. But instead of relieving himself, he took the Roman equivalent of toilet paper—a stick with a sponge on the end—and shoved it down his throat, suffocating himself. Grim stuff. So, it wasn’t all beer and skittles.

What we do know is that thousands of men, beasts, and prisoners of all kinds died in the amphitheatre, presumably to the roar of the crowds—a roar that has echoed across millennia to this day. No longer on the bloodstained sands of the Colosseum, but at the racetrack, the football pitch, and the boxing ring. While these sports don’t aim for blood and gore, many love watching the crashes in F1 or the brutal highlights of a heavyweight boxing match. We must remember, we are still the same species that once sat in the Colosseum calling for blood. It wasn’t that long ago that public executions were attended, and people still seek out horrific war videos from Ukraine or the Middle East.

So, that’s all for this week. I hope you have enjoyed my attempt to paint a picture of the Colosseum, and share with you some stranger anecdotes from the past. Join us next week for part three of Gladiator, where we’ll take a look at Commodus, his short, sharp reign, and all the fun he had in the arena. All that, and more, in next week's History vs. Hollywood.

Well, actually…

In this part of the newsletter we dig up some interesting bits that have not made it into the main story.

When Maximus escapes from his would-be executioners in Germania, he makes his way home—presumably to Hispania. From the Danube, this would be a journey of anywhere from 1,500 to 2,000 km, a trek that would have taken weeks, if not months, in Roman times. It would have involved crossing mountains and enduring a generally unpleasant experience. Not that a tough guy like Maximus would have found it impossible, but it certainly would have been a hard journey. Following that, when he is captured after finding his home in ruins, he is presumably taken to Roman North Africa, specifically Zucchabar, near modern-day Algeria. This would be another journey of 2,000 to 2,500 km, depending on whether they travelled by land or sea. So, poor Maximus endures a lot of travelling. It’s also incredibly unfortunate that the first people to find him were some opportunistic souls who saw a man on the brink of death, surrounded by his dead family, and thought, "I can make a few quid selling him."

There were many different styles of gladiator: the retiarius, the net fighter; the murmillo, the fish-helmed warrior; the Thracian, who carried a small buckler-style shield and leg greaves; the essedarius, who fought from a chariot; the laquearii, who used a lasso; and, bizarrely, the andabata, who was supposedly blindfolded (I can’t imagine they won very often, but perhaps it helped with the nerves). This was not a fixed list, as the styles changed over time, of course. It is most likely, then, that Maximus would have fought like a secutor, armed similarly to a murmillo but carrying a larger shield, which, funnily enough, is the same style favoured in real life by his erstwhile enemy in the film, Commodus. More on him next time.

Conclusion

And that’s it for this second part of our Gladiator series. Next time we will be heading back to the narrative of the film and taking a deep look at Commodus, the antagonist in Gladiator. What was he really like? Did he actually fight in the Colosseum? Was he as bad as he is made out to be? And as always, we will have plenty of weird and entertaining anecdotes for you. Hope to see you there.

If you have enjoyed this, have any comments, requests for clarification or would just like to chat about this newsletter or the subject of this series, please let me know in the comments below. To support my work in the best way, you can add me to your recommendations if you are a Substack writer yourself, share this with anyone you think might enjoy it, subscribe for free so you get notified when the next chapter is released, and hit the like button.

Thanks for setting the record straight—I had wondered if there was any documented footing behind the “Christians fed to lions” narrative. Hadn’t heard that women would readjust their clothing after being mauled—-sounds very realistic:)

Well written and engaging!

What’s the difference between a pig fighting in an arena and a man who just finished a delicious pork chop?

Ones a gladiator pig and the others glad-he-ate-a pig!