Episode 7 | Braveheart - Part 1: Why Did William Wallace Need to Lead a Rebellion in the First Place?

A towering giant with a massive sword leads the Scots in an epic rebellion—at least, according to Braveheart. But how true is the legend? Find out in this week’s History vs. Hollywood.

Love historical films? Join History vs. Hollywood to explore the real stories behind the movies you love, with humorous insights backed by the best historians and exclusive artwork. Subscribe for free and dive into the truth behind the screen!

I have an exciting announcement to make. If you would like to listen to this episode instead of read it, you can now do so! With each episode I will be releasing a companion podcast. In this I will be reading the episode out loud, but also plan on adding in some extras, like answering questions from the readers and so on. If you would like to check that out so you can listen to History vs. Hollywood on the go you can do so below!

The Film Narrative

A green and bonny land, home to a proud and fierce people, their love of liberty only eclipsed by their passion for fighting and laughter. But all is not well in this pleasant idyll, for a power beyond their supposed might circles and waits for opportunity. The hated English and their King, Longshanks, seek to make Scotland their own.

Treachery is his favoured weapon. Under a white flag of truce, Longshanks invites the Scottish nobles to a meeting and kills them all. Malcolm Wallace and his sons are the only survivors, and they gather their strength to strike back against their would-be southern oppressor. Although they have heart, they lack the means, and they are slain for their efforts, leaving young William heartbroken and alone.

Taken in by his uncle, William is taught not only how to be a man, but to use his mind. Yet he longs for the land of his childhood and returns to his father’s farm as soon as he comes of age. There, he reconnects with friends, both young and old, and meets the love of his life, Murron. In secret, they marry, and their happiness knows no bounds.

But all is not well in the land of the Scots. Like a cancer, the English corrupt everything they touch. From Prima Nocte to the harsh occupation, happiness finds no place in this land. William’s love is taken from him, and his heart hardens. Leading his friends, he drives the English out of his home. An outlaw now, he knows what he must do if his people are to be free.

The Real Historical Narrative

Hello and welcome to History vs Hollywood. This is the first part of a three-part series on the absolutely epic 1995 film Braveheart, directed, produced, and starring Mel Gibson. It tells the tale of William Wallace, the hero of Scottish independence, who fought to free his country from the English at the end of the 13th century. Not only that but it features one of the most beautiful scores in film history

In this first part, we will explore the context and setting of the film, the relations between England and Scotland at the time, the succession struggle, and how a young William Wallace fits into all of it. I can’t wait to dive into the details with you over the next three weeks. So, let’s get into it.

Before I get started, I want to share my source for this series. The problem with William Wallace is knowing where the myth ends and the truth begins, as the details of his life are surprisingly hard to piece together. There is no real consensus on when he was born or even exactly where, so this whole series would have been impossible without the excellent and well-researched William Wallace: Brave Heart by James Mackay. I am in no way affiliated with the author, but if you fancy picking up a copy, you can do so here.

Braveheart is an epic tale of Scotland’s struggle for freedom from Edward Longshanks, known as the Hammer of the Scots. It portrays William Wallace, a noble farmer who, outraged at the murder of his new wife, leads a rebellion to try to remove the English oppressors from his land. Mel Gibson delivers an epic performance, and the film is hard to fault, even at almost three hours long. But is any of it really true? For the most part, the story isn’t completely made up, but it’s not exactly presenting the facts as they are available. It leans more into the mythology around Wallace than the actual truth.

So, what was going on in the Scotland of William Wallace’s youth? Why were the English there in the first place? What happened to trigger Wallace’s rebellion against the crown?

Now, I know this may come as a shock to most readers, but things were actually fairly calm between England and Scotland in the latter half of the thirteenth century. For those unfamiliar with English and Scottish relations, they’re usually frosty at best, outright hostile at worst. But in the decades preceding the birth of the erstwhile hero of Braveheart, things had been going well.

Scotland was ruled by Alexander III, and he was doing a pretty good job of it. Coming to the throne in 1249, he had ruled effectively, seemingly fairly, and had even managed to expand the Scottish realm without upsetting his neighbours too much. Some even go so far as to suggest that his reign could be described as a golden age for the recently named Scotia—not just in the noble peasant, rural-idyll style of a golden age either. Scotland was booming. Roads were being built, cities were popping up left, right, and centre, and port towns like Berwick were attracting traders from all over the world. One mediaeval visitor described Berwick as a "new Alexandria," so rich was its bounty, though I imagine with slightly poorer weather. Most of Scotland's trade was with Scandinavia and mainland Europe, and surprisingly, not with its southern neighbour, England.

To add more to your understanding of Scotland at the time, it wasn’t just a rural backwater full of peasants tilling the earth and living a hard but honest life. Scotland was really on the rise in the mid to late thirteenth century. Beautiful abbeys and monasteries were popping up all over, and castles were springing up wherever you looked. Cities like the aforementioned Berwick were not the only places booming either. Industries like shipbuilding were flourishing in places like Inverness. Pound for pound, Scottish agriculture was doing better than England’s at the time, with wool exports amounting to almost 20% of the total value of England’s trade. Silver was flowing freely, evident in the high-quality coinage discovered from the period. The Scots had done away with serfdom, taxes were low, and people were even starting to live in stone houses in some of the cities.

All this success meant Alexander III had cash to spare. For example, he personally bought the Western Isles in 1266 for four thousand marks. By comparison, the ruling house of England, during a similar period, saw Henry III requesting an extension on payments of the dowry for Alexander’s first wife, Margaret, as he was strapped for cash.

Money matters aside, relations were good between the neighbours. Because the borders had never really been defined, the Scots had historically had a habit of trying to annex Northumberland and other desirable parts of northern England. However, Alexander had no such ambitions, instead focusing on less controversial territories to conquer, such as the various islands surrounding Scotland. Under Alexander, the frontier effectively lay in a straight line from the Solway Firth to the Tyne River.

The actual relationship between the Scottish and English kings had never really been defined, and this was to cause a great deal of trouble by the end of the century. The problem all started with the Normans. When old Billy the Conqueror sailed to England and took over in 1066, he used baronage to divide up his new kingdom and have it ruled by a selection of his favourite toughs. A few centuries later, the descendants of these French warlords were often still in place. Some of them had even risen to such lofty heights as Kings of Scotland.

This made things a little complicated because the lords and rulers of Scotland were also English magnates. So, were they subservient to the English crown, then, or not? This question had always, and would continue to, cause a fair amount of trouble. It was unclear, but for the time being, Alexander was doing a fairly good job managing it.

The Scottish kings had always done homage to their English counterparts for the land they owned in England. Doing homage is a rather embarrassing ceremony that involves the person in question coming to the king, grovelling a bit, and then acknowledging the king’s right to ask him to do whatever he likes. You can see why that might complicate your sovereign rule over a nation like Scotland.

Attempts had been made to clear this up. In 1174, a Scottish king at the time got himself captured after an unsuccessful attempt to retake Northumberland. Henry II of England threw him into jail and only released him after he acknowledged Henry as his liege lord. In return for his freedom, the Scot paid homage to Henry. So, there you have it—problem solved, the English are in charge, right? But not quite, because a generation later, Richard the Lionheart, an English king far more interested in crusading than ruling England, sold this agreement back to the Scots to pay for his crusades. So, not quite resolved then.

When Alexander III came to power, his father-in-law, Henry III, asked him to do homage in return for his daughter’s hand in marriage. Alexander, a young man then but already showing signs of being a strong captain for team Scotland, politely but firmly refused. Since then, Scottish and English relations had been cordial, but perhaps a little chilly.

As I’ve already mentioned, Alexander was a pretty decent monarch. His only real shortcomings in that regard were his lack of an heir and his nocturnal horse-based navigation skills, more on that later. As children often did in those days, Alexander’s kept dying. His youngest son died unmarried, and his eldest died a few years later, married but without an heir. This meant that when his daughter died in childbirth, leaving a girl baptised Margaret—soon to be more famously remembered as the Maid of Norway—the succession fell to her. A foreign child and a woman to boot—these were not strong succession plans in the thirteenth century. We will return to the Maid of Norway in a moment but for now, let's introduce a character who will shake things up significantly in Scotland.

Edward I, or Longshanks as he was known for his famously long legs, came to the throne following the death of Henry III. It makes for a rather good story that both Edward and William Wallace were famously tall, good-looking chaps. Edward was crowned at 35 and set about getting on with the business of kingship.

He was a pretty formidable guy, having already been involved in several wars that he had brought to successful conclusions before being crowned. He’d even done the coolest thing a mediaeval knight could do—he had been on a crusade, the ninth one, wouldn’t you know. Shortly after being crowned, he crushed a rebellion in Wales, but when it didn’t quite take, he returned in the 1280s and conquered the whole country. To keep Wales pacified, he built a string of forts and towns, settling them with Englishmen. This did the trick and was a lesson he would remember when he turned his attention to Scotland in the near future.

Besides being good in a fight, Edward was also adept in the courtroom. He spent much of his reign fiddling with and straightening out the antiquated and confusing laws that governed his realm. He would later use his lawyerly skills when dealing with a series of unfortunate events involving the Scottish royal family. These events would set the stage for the epic tale told in Braveheart. But before we get there, we need to return to Alexander III and his troubles riding horses at night.

It was a dark and stormy night in mid-March 1286. The vibes were bad, and omens and evil portents were being reported all over the place. King Alexander, however, was not a man to be frightened by such things. Rumour has it that he had recently been told his horse would be the death of him, so being an efficient problem solver, he had the horse killed. After a raucous good time feasting with his chums in Edinburgh Castle, he decided to pop out for a nocturnal foray to another of his residences, Kinghorn. Perhaps, having eaten and drunk his fill, he fancied topping the night off with a roll in the hay with his new wife.

The only problem was that a storm was brewing. His advisers begged him not to go, but he was a king, and a Scottish king to boot. No Scotsman worth his salt would be afraid of a bit of rain, so he hopped onto his new horse and went on his merry way. He was accompanied by a few friends and squires, but as they made their way home in the dark, the wind picked up. Along the way, most who saw him tried to convince him to try again in the morning, but he was a wilful chap and marched on. This was not his first rodeo, he told himself. Sometime after crossing the Firth of Forth and beginning the eleven miles of terrible road to Kinghorn, disaster struck.

No one is quite sure what happened, but there are rumours it went something like this:

The wind had reached a howling gale. In the noise, darkness, and general confusion, Alexander was separated from his party. He wandered unknowingly toward the cliff edge when, slowly, a shape began to appear in the mist. His horse wickered, but he urged it on. The shape was large—well, as large as a horse, in fact. Suddenly, a flash of lightning revealed the corpse of his old steed. His new horse, driven mad with fright at seeing the corpse of its old stablemate, reared up, and Alexander, full of good wine and meat, lost his seat. He tumbled backwards, off the horse and over the cliff edge. Landing with a ‘thwack,’ Alexander broke his neck, killing him instantly. As the light faded from his eyes, so too did the light fade from Scotland's golden age. The omens and portents heralded the beginning of a bloody and violent new era between Scotland and England.

Well, that could be how it happened—nobody is quite sure. This version is fun, so let’s go with that. What is certain, though, is that Alexander III was found the following morning very much dead. Unfortunately for Scotland, he had not left them a strong heir, and so began the series of events that would lead to William Wallace’s rebellion and the inspiration for Braveheart.

As I previously mentioned, it seemed likely that Alexander was on his way back to his young bride, Joleta. Perhaps that would have been the night he sired himself an heir. But alas, it was not. A few weeks after his death, the nobles gathered and swore an oath to Alexander’s granddaughter, Margaret, the Maid of Norway. In the meantime, they also set up a provisional government to rule until she could pop over from Scandinavia. The nobles, all seemingly pleased with the arrangement, shook hands with fingers firmly crossed behind their backs and returned to their respective castles. Before long, factions began to form.

Given that the Maid of Norway was only three years old when she was “crowned” queen of Scotland, she stayed with her father, Erik II, in Norway. Talk about pressure—only three years old, and someone makes you monarch of a country you’ve presumably never heard of, nor speak the language. It would be about four years before she sailed to her new home, which left ample time for the lords and nobles to make a mess of things in Scotland.

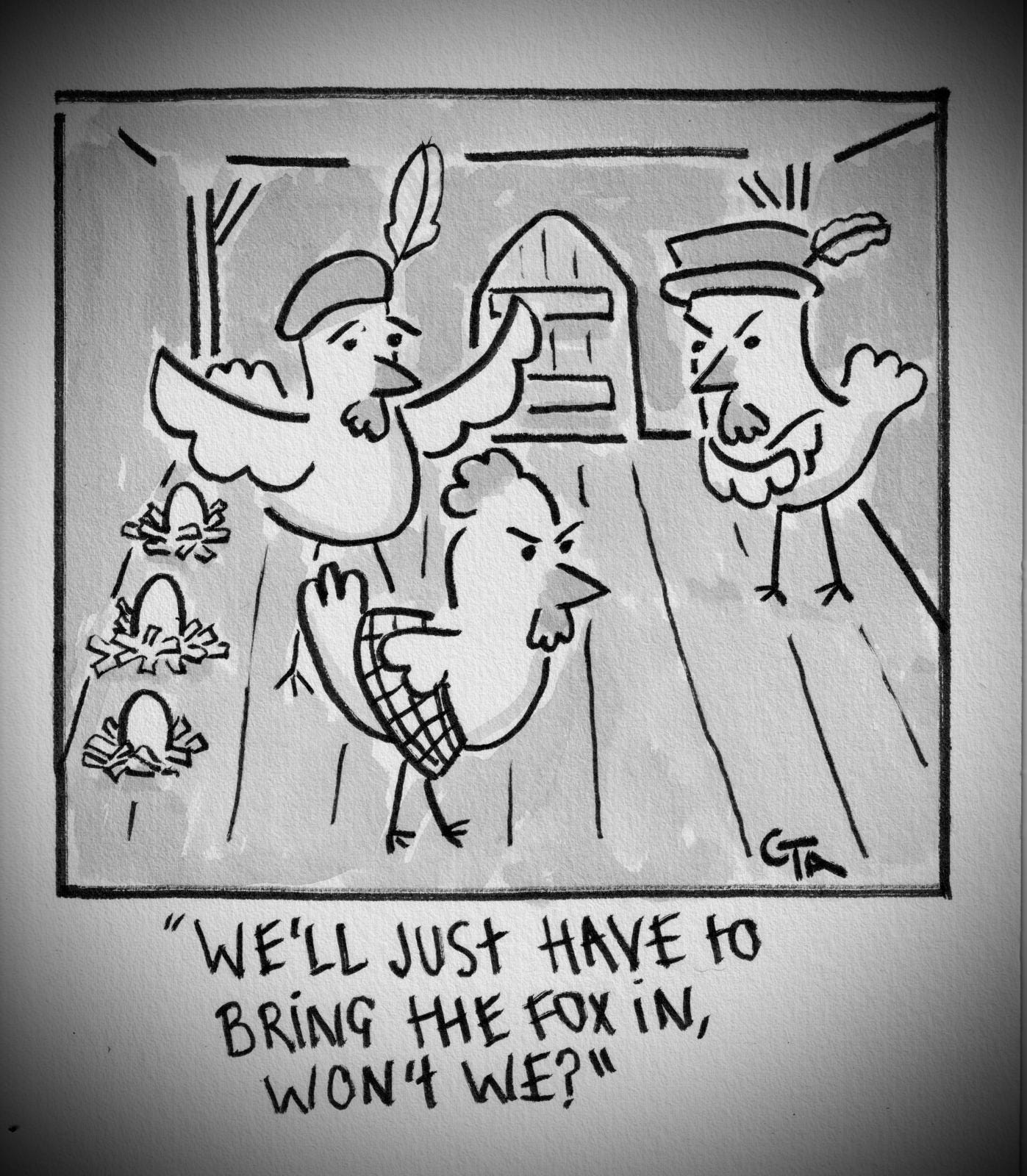

In Braveheart, you get a glimpse of these factions when William Wallace is declared Protector of Scotland, and they all begin bickering about who has the best claim to the crown. It seems pretty spot-on, because believe you me, these guys liked an argument. The Scottish nobles had a strange mix of Norman and Celtic connections, leaving them very open to having their loyalties tugged left and right. You had the Bailleul Family on one side and the Brix Family on the other. Neither are very Scottish-sounding names, but you may have heard of their more widely used versions by the late thirteenth century: the Balliols and the Bruces. Oh boy, did they both fancy themselves King of Scotland.

In an effort to keep things cordial with their particularly scary neighbour down south, the Scottish guardians decided it was best to keep Longshanks in the loop. They sent a letter to him in Gascony that may have read something along the lines of:

"Hey Eddie, things are good up here. How's France treating you? I've heard the weather is great this time of year. Just letting you know that the Bruces and the Balliols are up to their old tricks and may go to war with each other soon, but don’t worry about it. Just thought you’d like to know. K, bye xx."

The message may have been intended to seek the advice of Longshanks, but he interpreted it the way he wanted to—as an acknowledgement of his overlordship of Scotland.

The Bruces then went and kicked the hornet's nest by invading Galloway. They quickly set about acquiring lots of Balliol land and, together with a few of their noble chums, declared themselves the "Turnberry Band." This was all happening under a set of dangerous precedents. In the preceding few decades, there had been a few occasions where the Scottish nobility had behaved similarly badly, requiring the English crown to intervene and "save the day." For example, in 1254, Alexander III had been kidnapped by a group of nobles— notably, Robert the Bruce, father of future King of Scotland, confusingly also named Robert the Bruce, was part of the conspiracy— and held hostage at an abbey. Henry III had ridden to the rescue, and as a result, Alexander III had been forced to acknowledge Henry as his superior.

So, when things got a bit feisty in Scotland this time around and the guardians called for help, Longshanks saw an opportunity. Since the death of Alexander, he had been quietly scheming in the background. His latest sally was very much a long-term plan. He was arranging the future marriage of the Maid of Norway to—would you guess it—his own son. This all meant that in the not-so-distant future, Scotland would effectively become his. Trivialities such as the fact that his son and the Maid of Norway were first cousins were swiftly overcome by a Papal Bull granting dispensation for the marriage. It seems the laws of the Church at the time were as flexible as you were wealthy.

By now, the Turnberry revolt had sort of fizzled out, and Edward had missed his opportunity for a full-scale takeover. He had, however, made use of the confusion to install hand-selected magistrates in certain Scottish territories, notably the Isle of Man—one of the fruits of Alexander’s reign—which was now, for all intents and purposes, an English territory. This brazen act of illegal occupation was a sign that Edward was perfectly happy to break his beloved laws when it suited him. The Isle of Man had, in fact, never been English and had been given to the Scots by the Norwegians in 1266.

It wouldn’t be long, though, before another unfortunate event would turn the whole Scottish succession issue on its head again and leave Scotland open and vulnerable to Longshanks. The wedding between Edward’s five-year-old son and the six-year-old Maid of Norway was fast approaching, and Scotland was abuzz with excitement over the upcoming nuptials. But it wasn’t to be. Tragically, it seems that the Maid of Norway fell ill on her journey to her new home and died soon after landing on the Orkney Islands. Thus ended the Scottish dynasty, leaving an uncertain future for all those who called Scotland home.

The real trouble began shortly after. The problem under Alexander had been a lack of heirs, now, there were too many. I won’t get into how many, as that would be incredibly tedious, but essentially every Scotsman with land reckoned he was a shoe-in. Let’s just focus on the two main troublemakers in Scotland: the Balliols and the Bruces. By the law of primogeniture, the Balliols had the strongest claim, but by the laws of who can shout the loudest about it, the Bruces did—or at least believed they did.

As soon as there was even a whiff of a rumour that the Maid of Norway was dead, the Bruces began to gather and arm themselves. Scotland was once again on the verge of collapsing into civil war, and the Bruces were, of course, right in the middle, stirring the pot. As the nobles began to pick sides, a chap named Bishop Fraser, seeing the writing on the wall, made a fateful decision and wrote to Longshanks for help.

Edward, as mentioned earlier, fancied himself a bit of a lawyer. So, when contacted by Fraser, he magnanimously agreed to come and help sort out the whole mess in the courtroom. He then quietly told his privy council that he had every intention of bringing Scotland under his rule and treating them the same way he had treated the Welsh. Divide and rule was the name of the game. Scotland was ripe for the plucking: they had no ruler, the magnates were at each other’s throats, they had no real national unity—Scotland had only really been one realm for a few decades at that point—and the preceding eight decades of relative peace had conspired to leave them sorely lacking in military experience.

Maintaining an army large enough to defend Scotland from the English invaders is expensive. If you would like to help me do so, you can upgrade your subscription and we can keep these green and bonny lands free from tyranny.

Want to support my work without committing to a monthly subscription? Treat me to a virtual coffee! Simply scan the QR code below to make a one-time contribution. Your support means the world to me and goes along way to helping me purchase research materials, support my artists and contributors and dedicate the time this project deserves.

A lawsuit was arranged to sort out the succession, and under the pretence of justice, Edward was to preside and decide who would wear the Scottish crown. There was a catch, though—if they wanted Edward’s help, the Scottish nobles were required to declare Longshanks as Lord Paramount of Scotland. Summoning all the Scottish nobles to England, he made his case that he was the rightful lord of Scotland; all they had to do was recognize it.

An entertaining side note: in an attempt to legitimise his claim, Edward had the clergy dig up anything they could find to support his case. He went back pretty far and ended up with a story about the grandson of Aeneas of Troy coming to a mysterious island called Albion, or Britain, and slaying a load of giants. He left the island to his three sons, who went on to rule England, Wales, and Scotland. Supposedly, the son who ruled Scotland was killed by an invader at some point, then avenged by the son who ruled England, and ipso facto, English kings should rule Scotland. That is a watertight case if I’ve ever heard one.

The Scottish nobles considered their estates in England and duly decided he was spot-on: Edward was indeed Lord Paramount of Scotland. They gathered at a place called Upsettlington, aptly named as presumably some were a bit upset, and swore their oath of fealty. However, there was a conspicuous absence on that fateful day, and here is where the Wallaces enter the story. Sir Malcolm Wallace, of Ellerslie and father of our hero William, had decided he was in no mood to bend the knee to an English king. Longshanks was not one to overlook such a blatant disregard for his authority. The Wallaces' days were numbered.

Meantime, Edward made use of his new power, and decided that by the law of primogeniture, the Balliols had the best claim to the crown of Scotland. John Balliol was to be crowned King John, more on him next week though.

This brings us, in a roundabout way, to the story of Braveheart, and that is where we will pick up next time. I hope you’ve enjoyed this instalment. Next time, we’ll introduce the Wallaces and, notably, young William himself. We’ll take a look at his youth and the events that led him to lead a rebellion against the English crown. On top of that, we’ll delve deeper into Longshanks’ treatment of Scotland and how he earned the nickname ‘The Hammer of the Scots.’ So, if that sounds interesting to you, please go ahead and subscribe.

Conclusion

You may have noticed that I recently turned on a paid subscription, so let me explain things a little. I hope to always be able to keep History vs Hollywood advert free and subscriber driven, so your support would be immeasurably helpful. The money would go towards paying the artists who contribute to our articles and buying research materials that make this all possible. I have no intention of every paywalling the episodes, and the weekly articles will be available to everyone, whether you are a paid subscriber or not. The support is totally voluntary on your behalf. One day, when I have more time, I will go about creating some perks for my paid subscribers, bonus episodes and so on, but honestly, for now I simply haven’t the time or resources. So, thank you again for your continued support, it means the world to me, and if you do fancy supporting me with a paid subscription, you can do so below.

As always, if you have enjoyed this, have any comments, requests for clarification or would just like to chat about this newsletter or the subject of this series, please let me know in the comments below. If you have enjoyed this, give it a share, follow me so you get notified when the next chapter is released, and hit the like button.

Great background info. I hope you are going to answer the eternal question. “Oi, Gibson, where’s the fucking bridge?”