Episode 3 | What really happened after The Battle of Thermopylae in 300?

The Spartans have been crushed by the Persians, and Xerxes marches on Athens. But what really happened? Let’s find out in this week’s instalment of History vs Hollywood.

The field of Thermopylae is littered with the fallen Greek defenders. Scarlet Spartan cloaks and blood paint the battlefield a colour as passionate as the Greeks' defence of their homeland. The Greeks Left to rot, until the Greek sun bleached their bones white, the Persian forces moved on.

It would be an age before wind and time had covered their graves, those brave few who stood for freedom and defied tyranny. All that remains now is a wish, a request, a simple ask. “Go tell the Spartans, stranger passing by, that here obedient to their laws we lie”.

But lie not the Persian forces, for into Greece they pour, looting and burning as they go, Athen, their ultimate prize has not long left for this earth. Dilios, the sole survivor, has rushed ahead of the Persian forces, and summons the Greeks to expel the Persians from their land.

A great force he amasses, and inspires with the tale of Leonidas and his brave few. Together, they will break over the Persian forces like an avenging wave, and drive them from their land.

First, a little bit about the newsletter: we are a film/history enthusiast publication where each week, we delve deep into the real history behind some of our (and hopefully your) favourite historical films. We’ll dissect the narrative of each film, act by act, and reveal the truth (as far as historians have gathered) behind the movie. I’m no historian myself, but I’ll be using the works of the best historians as my sources, hoping to bring you an entertaining look at what really went on and inspired these great movies. This is a free passion project for me, but I would greatly appreciate your support by following, clapping, or liking if you’re on substack (see the button below), and sharing this with anyone you think might be interested. Thanks for now, and I hope you enjoy this instalment of History vs Hollywood.

The Real Historical Narrative

Before we get started, let me give a big shout-out to my main source for this series, Persian Fire, by the fantastic podcaster and historian, Tom Holland. A fountain of knowledge, as well as a great read, please get hold of a copy if you want more details about this whole slice of history. I am in no way affiliated with this at all, but you can follow this link here to get hold of a copy here.

In last week’s instalment, we covered the Battle of Thermopylae itself, the betrayal of Leonidas by Ephialtes, and finally, the glorious Greek last stand. If you would like to catch up, you can find last week’s article here. This is part 3 of a 3 part series, so maybe you want to start from the beginning if you are just joining us now. As this is essentially where 300 ends – and honestly, I cannot bring myself to talk about the second 300 film as it is just absolute garbage – I will try my best to guide you through what happened after Thermopylae and the conclusion of the Greco-Persian War. We have epic sea battles, double agents; lots of blood, and all that good stuff with a smattering of Hubris to top it all off. So, let’s get into it.

Xerxes, unlike in 300, did not deign to grace the Hot Gates with his presence until the Greeks were well and truly dead. Xerxes had, as most Persian princes do, proved himself plenty handy on the battlefield in his youth, and had no intention of risking the rule of the world’s greatest empire by getting himself within stabbing range of an angry Spartan. When he arrived he would presumably have been quite pleased. He had steam rolled the Spartans in only a few days, not a bad result in the end. However, a fair number had gotten away, not least of which was the combined Greek navy that I briefly mentioned in last week's instalment. This was not part of Xerxes’ plan.

The Greek navy had been present throughout the battle of Thermopylae, covering Leonidas’ flank. They had been based out of a place called Artemisium, a little ways up the coast. Throughout the six days of the battle, they had skirmished with the Persian fleet, and even had a fairly large pitched battle. Due to being vastly outnumbered by the Persians (and we are talking some 1200 ships on the Persian side to about 300 on the Greek), the Greeks had had to make sure that when they did engage the Persians, they did it in the narrow straits between Artemisium and mainland Greece. Unlike on land, where a narrow point of attack meant larger numbers couldn’t add an advantage, at sea, they almost invariably became a disadvantage.

The trireme, a sort of massive pointy ship with 3 banks of oars on each side, doesn’t work very effectively if it keeps smashing its oars to pieces on its neighbours as they are a bit short of space. In light of this, the Greeks held the Persians off, then managed to steal away in the night, once they had heard of Leonidas’ death – back south towards Athens and to temporary safety. Rightfully angry that they had escaped his wrath, Xerxes gathered his forces and set off towards his main target of vengeance. Athens was to be swiftly and totally destroyed.

It is time now to introduce you to a character that has so far gone unmentioned in this tale, but has been busying himself in the background tirelessly: Themistocles. A true blue Athenian, a massive fan of democracy and all the opportunities it could afford him. He was a born politician, one of the first to truly figure out how you could use public opinion to get just what you want: spin something as in the interests of the many, but make sure it also helped out the few—namely, Themistocles himself. A man of decidedly questionable character; nonetheless, without him, it is very unlikely that there would be an Athens or Sparta at all for us to talk about today.

Before we go further, it might be of interest to talk a little bit about democracy in Athens at the time. The world's first democracy, and definitely an inspiration for the version of it we enjoy in large parts of the world today—though, thankfully, not a carbon copy. I’m not going to go into the details too much, but in Athens, as long as you were a man born an Athenian, you had a vote equal to that of all others with the same credentials. Athenian politicians who could sway the masses generally got their way. Themistocles was this sort of guy. His big thing was boats. He absolutely loved them, or at least was convinced that they would be very handy should the Persians come back. He was, of course, in the end correct, but more on that later.

Athenian democracy seemed to take issue with those who were always right. Athens had a long history of exiling clever clogs and ensuring that anyone who had done anything particularly impressive didn’t get too big for their boots. Even Miltiades, the hero of the Battle of Marathon, ended up imprisoned for treason shortly afterwards; the Athenians were not ones for gratitude. Themistocles’ desire for the Athenians to build a navy felt just a little bit too much like someone aiming for the big time and as such, was of course, bickered over incessantly.

As I have harped on repeatedly, Greeks of this time period loved nothing more than an argument, so why would now be any different? Themistocles, being a man of considerably questionable character, had many enemies. His notable frenemy turned enemy was a chap called Aristeides. Both had fought together at Marathon; however, while Themistocles was a silver-tongued politician, notorious for bribing to get his own way, Aristeides was a supposed “Good Guy”. They even gave him the nickname “The Just”. They argued bitterly about the building of the fleet, mainly because Aristeides wanted to focus on hoplites doing hoplite stuff, and Themistocles wanted to build a fleet so he could essentially be the admiral of it. This interminable bickering went on so long that Athens finally had enough and went about breaking the deadlock by inventing a term we use to this very day: ostracism.

The people would vote on who they most wanted rid of—Themistocles or Aristeides—and whoever lost had to pack up their things and go into exile for ten years. That’s how annoying the pair must have been. Not only did they want the quarrelling to end, but they also wanted the loser to leave for a decade. Luckily for Themistocles, and in turn, Athens, he won. The fleet was built, and Aristeides made himself scarce for the time being. Perhaps going around referring to yourself as “the Just” rubbed people the wrong way.

Back to the aftermath of Thermopylae, and Themistocles and his fleet had already played a vital role in the defence of Artemisium. They fled back south to Attica, the land around Athens, to help with the evacuation. Surprisingly, in Themistocles’ absence, the Athenians had not really gotten around to actually evacuating anyone. Ever stubborn people, the Athenians, it would take Themistocles haranguing and bullying them onto the boats.

One problem was that Athenian men were so conservative, and let’s face it, downright odd about their women, that they considered it improper to even mention their names in public, let alone have them be seen. As such, they hardly wanted them making their way down to the boats to take them to safety—imagine the scandal of a decent Athenian woman being seen outside, even when fleeing for her life. Like I said, the Athenians are stubborn people. Slowly, Athens’ population drained out and onto the boats, where they would eventually end up in one of two places. The women, children, and the elderly were put up with a friendly neighbouring city-state, Troezen, and the men went to Salamis.

Salamis is an island off the coast near Athens. It would go on to serve as the fortress and staging post for the Athenian fleet as they awaited the approach of the Persians. With the usual amount of squabbling, Themistocles managed to convince the combined Greek navy, made up of squadrons from cities not always on the best terms with each other, to stay put on Salamis rather than returning piecemeal to defend their homes. Call it self-preservation, but Themistocles knew that their best bet was to stay together.

Pulling everyone back to Salamis did mean one unfortunate thing: the road to Athens was very much open. The Spartans and their neighbouring allies were fortunate enough to be tucked away behind the Isthmus, a small, easily defendable gap of land that joined the Peloponnese to mainland Greece. The Athenians, who I am sure were terribly aware of the unfairness of geography, had nowhere to hide.

You might think that as they had managed to evacuate everyone from Athens (almost, at least—more on that later), they would not be all that upset. The Athenians, however, had a peculiar feeling about their homeland. They derived their sense of statehood very much from the ground of Athens itself. It really was the actual geographic location of Athens that made them Athenians. As such, in their opinion, they couldn’t very well just go off somewhere else and remain Athenian. This meant that when the Persians came—and they certainly would—the loss of their city would be keenly felt by the survivors on Salamis.

From Salamis, the survivors had no direct view of the Persians approaching Athens, with Mount Aigaleus blocking their line of sight. Those who had decided to stay in Athens, on the other hand, had the best seats in the house. Earlier, the Oracle at Delphi, in typical Delphic fashion, had told the Greeks that they were essentially going to get steamrolled by the Persians, but that “only the wooden wall will stand.” Themistocles and company had taken this to mean that the navy would be the deciding factor; some, on the other hand—rather foolishly, if you ask me—had taken to believing that the wooden palisade around the Acropolis in Athens would be the rock against which the Persians’ hopes of victory would be dashed.

The defenders, having all pulled back to the Acropolis, would have had to watch as the massed hordes of the Persians channelled into their city and did what armies usually do in such circumstances: began looting. All of Athens’ treasures were to be boxed up and shipped back to the heart of the empire, presumably to be gloated over once victory was complete.

Xerxes got swiftly to the business of siege craft. Taking one look at the newly built wooden defences on the Acropolis, he ordered his archers to riddle them with burning arrows, setting them alight. That dealt with that. Perhaps the defenders, remembering the Delphic Oracle’s words, began to think that this wasn’t the wooden wall she had referred to. The Athenians put up an admirable resistance, but they did not consider that the Persians were originally a mountain people. With the defenders occupied at one end of the Acropolis, a number of Xerxes’ elites simply climbed up the cliff at the other end, facing no resistance at all. They fell upon the Athenians and made short work of them. Such was the end of Athens.

To the Athenians on Salamis, all they could see was smoke rising from behind Mount Aigaleus, but they knew very well what it meant. The very place that had made them who they were was gone. And to add insult to injury, the other Greeks immediately started referring to the Athenians as “men without a country.” A really lovely bunch, these ancient Greeks.

This, of course, sent shockwaves through the Greek forces, as most of them decided all was lost and that it was better to nip home and defend their own cities while they could. Fortunately for the Greeks, they had in their midst good old Themistocles, a man supremely good at convincing people to do something they had no interest in. The Athenian had the advantage of growing up under democracy and, as such, had had to argue more bitterly than any of his opponents to get anything done. They were no match for his rhetoric, and as Xerxes tightened the noose around Salamis and the remaining Greeks, Themistocles managed to convince them all to pull together and stick it out.

That same prophecy from Delphi I mentioned earlier also had a line about “Divine Salamis.” The Oracle warned that it would be the “ruin of many a mother’s son.” But whose mothers? The Greeks, although they considered themselves firmly the centre of the world, were under no illusions that they were the only part of it that the gods paid attention to. Xerxes had made a big show of going to the ruins of Troy on his way over from Ionia and sacrificing to Athena. Perhaps he meant to show that there would be no hard feelings, as he was about to lay waste to a city that was her namesake. On the other hand, perhaps this had done the trick, and the gods were firmly on Xerxes’ side. The Oracle at Delphi’s business model was essentially receiving bribes in return for favourable advice, so the chances are slim that Xerxes’ vast gold resources had not made their way into the Oracle’s coffers. The Greeks would have been aware of this, and as such could not be sure which way this would all play out.

It would be decided on Salamis then, one way or the other. Xerxes’ squadrons closed in on Salamis, and the Greeks holed up and did what they did best: bicker. Xerxes’ spies were certainly among the Greeks on the island, and word made it back quickly that the Greeks were behaving just as he would have wanted them to. It wouldn’t be long until this unnatural coalition broke up and the Persians could pick them off one by one.

Xerxes wanted a decisive battle, and he wanted it quickly. He was, after all, a pretty important guy, and to be seen wintering outside the empire in some sort of strange, B-list backwater like Greece would not do for his public image. The problem was that he had seen the Greek navy and what they could do at Artemisium; it was best not to engage them in narrow channels, such as the one the Greeks were using to protect their fleet at Salamis. He would do what the Persians had always done—foment the squabbling amongst the Greeks—and wait for the perfect opportunity.

Perhaps Xerxes had gotten a little too confident after his crushing victory at Thermopylae, the easy conquest of Athens, or maybe even the 60 or so years of divide-and-conquer tactics he and his predecessors had used to such great effect on the Ionian Greeks. As such, it never crossed his mind that all the bickering going on in Salamis could have been for show. Themistocles and his allies may very well have been telling the King of Kings exactly what he wanted to hear.

Xerxes knew gold could be used to turn even the most loyal man away from his cause, and so must have had no consternations when brought before him was a slave of Themistocles, sent by the man himself, with a juicy tidbit of information. The Peloponnesians, having had enough of the rest of the Greeks, were planning on making a break for it in the dark. Block their escape, Themistocles' message conveyed, and victory was assured. Now, it is all a bit fuzzy and lost to the mists of time, but it seems that for some reason, Xerxes was convinced by this message. Themistocles had turned his cloak, most likely with the expectation that he would be rewarded handsomely. Unfortunately for Xerxes, this messenger sent by Themistocles was pulling a fast one.

Xerxes gave the order, and his fleet took up station, blocking all the escape routes from Salamis and awaiting the fleeing Greek ships. In the meantime, in what can only be described as an act of supreme hubris, Xerxes had his throne placed on a cliff on the mainland so he would have the best seat in the house to watch his final victory.

The sun rose over the Aegean, illuminating the shattered ruins of what Xerxes hoped would be the Greek fleet and their hopes of independence. To Xerxes’ surprise, what he saw was in fact the full Greek navy, in formation, ordered, and battle-ready, with his squadrons still blocking the escape routes from Salamis.

Now, no one is quite sure exactly why what happened next happened, but for some unknown reason, the Persian fleet charged—right out from the open ocean, where their numbers assured certain victory, into the narrow strait between Salamis and the mainland, where their numbers meant almost certain defeat. The Persians became a tangled, disordered mess, and the Greeks fell upon them like wolves, picking them off one by one.

The battle quickly faded into a frothy, bloody maelstrom. The Greeks, lost in a frenzy, drove the Persian fleet into the depths. The actual details of the battle are hard to grasp, as most of the Greeks came back talking of great sea monsters, apparitions of long-dead heroes, and the crashing of godly voices across the battlefield. What we do know is that the Greeks trounced the Persians and destroyed their fleet, effectively ending the Persians’ naval presence in Greece.

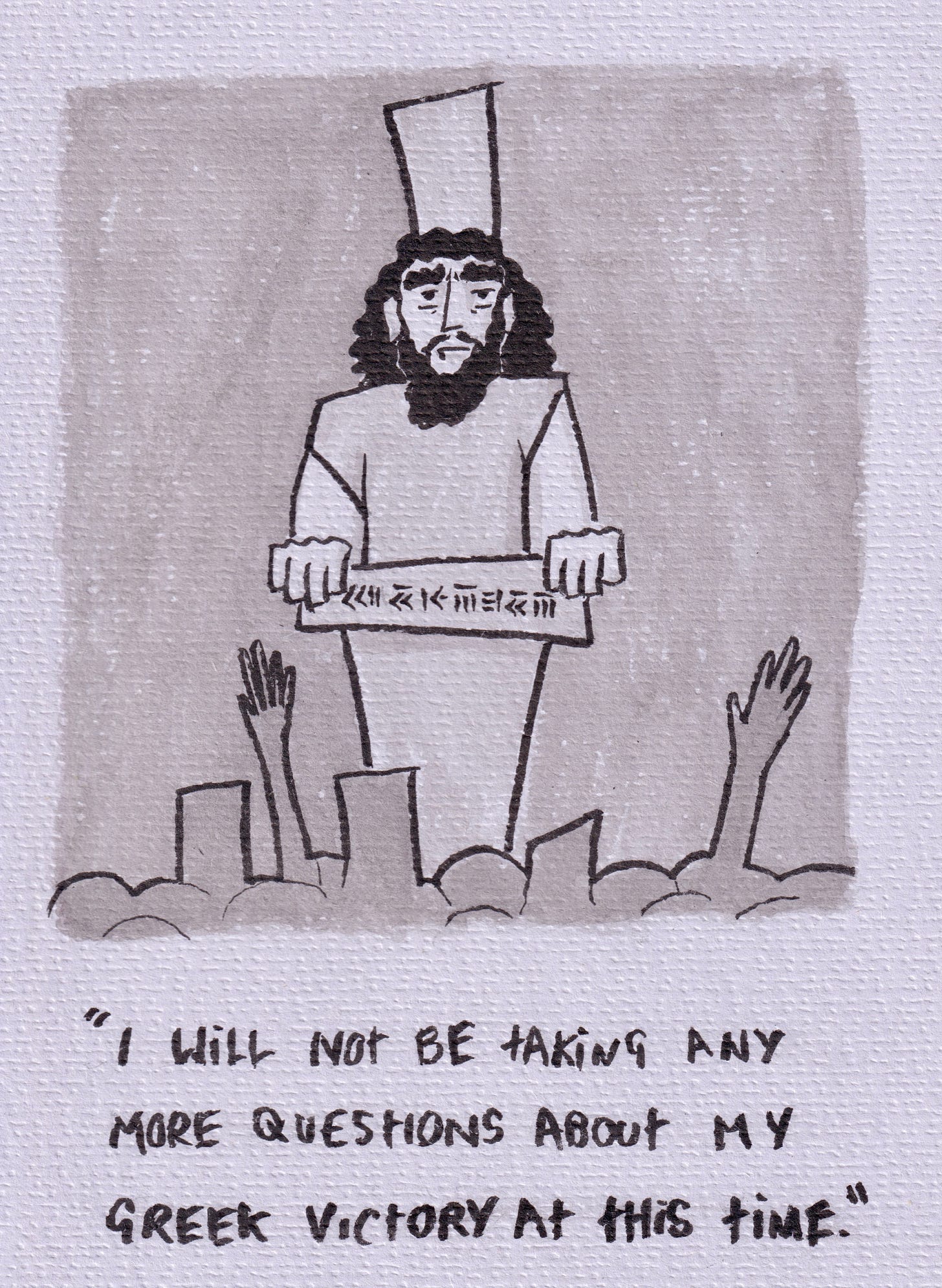

And yes, whilst all this unfolded, Xerxes sat upon a throne that had been specially installed for him to watch the battle. You can imagine the nervous fidgeting of his staff and advisers as the disaster unfolded. Did Xerxes sit in stunned silence, or did he burst into an uncontrollable rage? Unfortunately, we will never know for sure. The Persians, perhaps because they lost or perhaps because it was fairly insignificant to them, make absolutely no mention of the war against the Greek mainlanders in their records. In fact, they considered their global rule so assured that they convinced themselves they had ended history, and as such, there wasn’t much point in jotting anything down. So we will never know, but what we do know is that shortly after the battle, Xerxes left the Greek peninsula and returned to his empire.

He could very well spin this as returning in victory. He had done many things he had set out to do—destroying Athens, whipping the Spartans and whatnot. It certainly didn’t seem to impact public opinion of him, not that this was really a factor in the Persian Empire, where everyone was considered a slave of the Great King of Kings.

As summer turned to autumn, the Greeks all gathered off the coast of the Isthmus, the narrow gap of land that was the only easy approach onto the Peloponnese. A good time was had by all, as they were fairly pleased with themselves. They had won a famous victory and were assured in their feelings of superiority to the effeminate, unworthy Persians. Needless to say, though, the war was not quite over. The reason they were meeting on an island off the coast was due to the large holding force that Xerxes had left behind when he had made good his return to his empire. This would need to be dealt with before any of the Greeks could safely return home.

As previously mentioned, due to the unfairness of geography, those who called the Peloponnese home were definitely in the best position. The Spartans had built defences across the Isthmus and, now that the Persian fleet had been dealt with, could quite comfortably head home—and promptly did so, quite literally leaving the Athenians holding the bag.

We are nearing the end of our tale now, so I will begin to speed things up a bit. Following Sparta’s return home, there was the usual back and forth of squabbling between the city-states: Athens asking for this, Sparta saying no; Athens pleading for that, Sparta ignoring them, and so on. The problem, though, was that the Persians were not a problem you could make go away by simply ignoring them. Eventually, this point landed, and the Spartans mobilised their entire army, joined up with their fellow allies who had now mostly grown sick and tired of maritime life, and gathered near a city called Plataea.

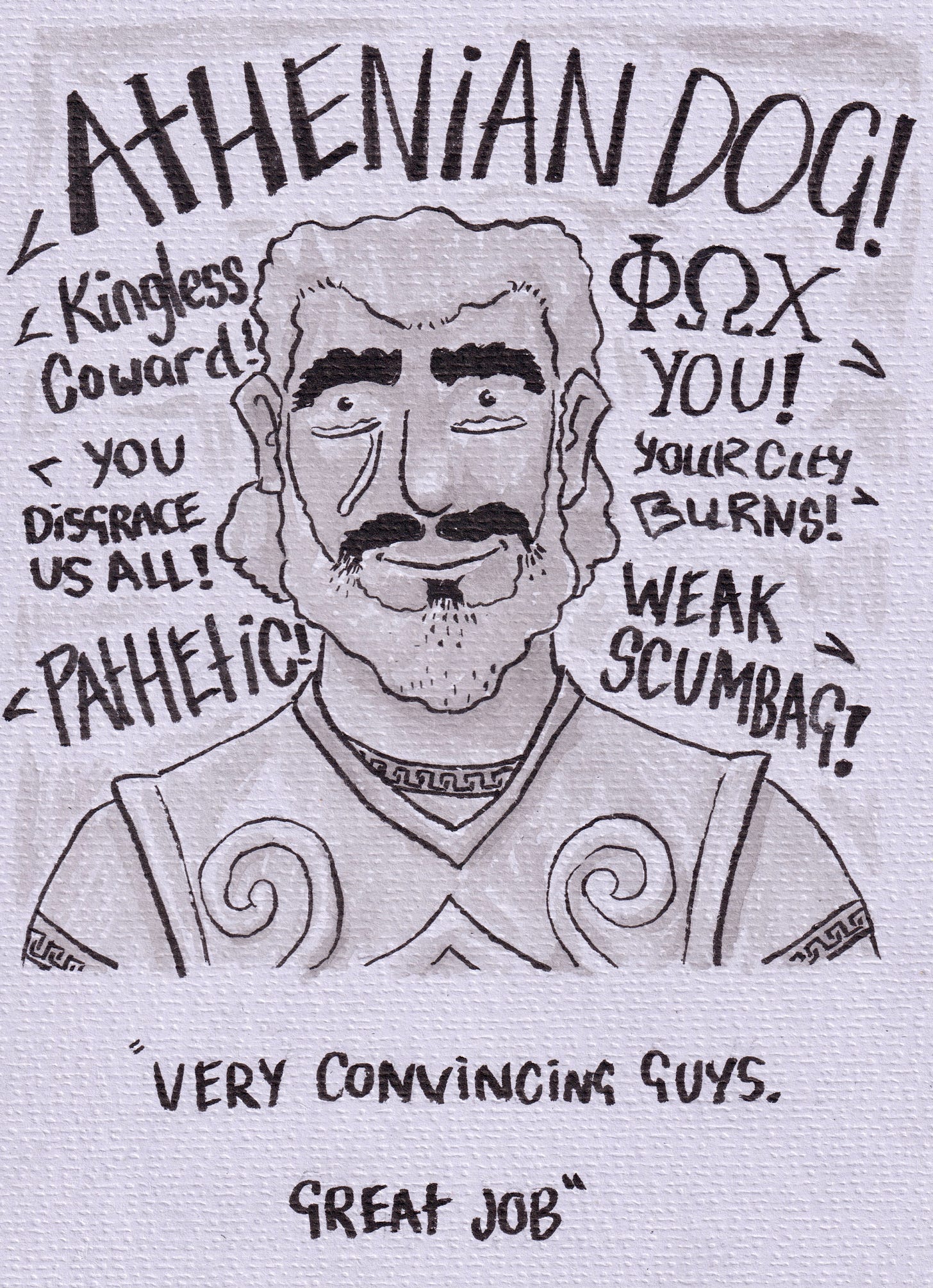

Here, the Greeks would battle with the Persians one final time. It is estimated that the Greeks mustered around 40,000 hoplites. Now, this is the battle portrayed in the final scenes of 300, and it brings us back to a character we discussed in the last instalment, “The Trembler.” It is with Aristodemus, the inspiration for Dilios, that we shall finish this series. As we said, he had been having a rough time of it in Sparta. Due to the unfortunate fact that he had survived Thermopylae, his countrymen had branded him a coward and were generally going about being unpleasant in a typically Spartan manner. His eyesight had recovered enough that he could make his way into the battle line at Plataea, and he was very much in the market for a chance to redeem himself.

Facing the Greek lines were the massed forces of Mardonius, a brother of Xerxes, numbering roughly twice their number. The forces that had been left behind by Xerxes were, let’s just say, not doing great. Morale was low, and they had now been away from their homelands for a number of years. They were, in essence, beginning to rot as an effective fighting force. The Greeks, on the other hand, were defending their homeland and were part of the largest force of hoplites ever assembled until that time. Not a bad morale booster.

Aristodemus and his bronze-clad companions had plenty of experience by now fighting Persians and knew that if crashed into at full tilt by a charging phalanx, they could be expected to crack pretty easily—especially if their structural integrity had been weakened significantly by years on campaign. Aristodemus knew this was his chance, in front of the massed forces of his country, to make up for what he had not done at Thermopylae, and so, before the hoplites charged, Aristodemus let loose his final battle cry and, alone, rushed the Persian lines. It is said by the survivors that he fought like a demon before eventually being cut down. His inspiration fired up the hoplites, and they crashed into the Persian lines like a thunderbolt, blowing away the weakened Persian forces in front of them. With sword and spear, they washed clean their homeland of the invaders and reclaimed the land of their births.

It was a great and crushing victory, with many killed on both sides. The outcomes were thus: the Persians were removed as an effective presence in mainland Greece, the Athenians could return to their blackened city and begin to rebuild, and finally, no one in Sparta ever said a bad word again about “The Trembler.” He had earned his place amongst the honourable dead of Sparta.

Fun Facts

Themistocles, our erstwhile hero of this tale, had fallen foul to good old Athenian jealousy. He had been so spectacularly correct about the fleet, sticking together, Salamis, that the Athenians couldn’t stand it and he was promptly ostracised. He wandered far and wide, most likely seething with bitter resentment for the un-grates in his city. Eventually, he ended up in the heart of the Persian empire, serving Xerxes’ successor. Eventually he made it out to Miletus, as a Satrap and spent his twilight years advising the Persians on how best to deal with the Ionian Greeks.

The Greco-Persian wars would signal the limit of westward expansion for the Persians. Originally they had all intention of conquering the whole world, but after Salamis, Plataea and hearing of a crushing defeat of the Carthanginians, an ally of sorts, by the Syracusians on Sicily, they thought best of it and their focus drifted elsewhere. The Persian empire would stand for a few more generations until the arrival of Alexander the Great, who perhaps wanted to make up for the fact that his namesake and grandfather had been more than happy to help the Persians in their earlier forays into Greece. That, however, is a tale for another time.

Conclusion

And that’s it for this first series. Next time we will be taking a deep look into the history behind Gladiator, with all its Russel Crowey goodness. If that sounds like something you would be interested in, consider following me on Medium, or if you are not a Medium subscriber, you can follow me here on Substack to get each article in your inbox for free.

Thanks again to my brother Charlie for contributing his hilarious sketches. Let me know what you think of them in the comments.

As always, if you have enjoyed this, have any comments, requests for clarification or would just like to chat about this newsletter or the subject of this series, please let me know in the comments below. If you have enjoyed this, give it a share, follow me so you get notified when the next chapter is released, and hit the clap button. All very helpful things to juice up the Medium/Substack algorithm.

I like how history refuses to follow a Hollywood script (with convenient heroes and villains) and run time. The real story is far more fascinating, and impossible to neatly fit into a movie.

That said, I was shocked in researching your next subject (Gladiator) at how closely the historical account and the movie script aligned. Looking forward to your coverage of it.

Love the sketches Charlie! Frank Miller is jealous